Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Overview of Key Statistics

- Section 1: Spouses versus Adult Children

- Section 2: Men versus Women

- Section 3: Caregiver Support

- Issue Spotlight: Cancer and Alzheimer's, a Tale of Two Support Systems

- About the Survey

- Contact a Caregiver

Introduction

The first ever AgingCare.com State of Caregiving report uses the results of an online survey of more than 3,300 family caregivers to dive deep into the demographics, financial circumstances, living situations and support systems used by people caring for an aging loved one. This analysis offers unprecedented information about this vitally important group of men and women.

As Americans' average life expectancy creeps ever upward, the need for family members to step in and take care of their aging loved ones will only increase. Currently, 36 percent of U.S. adults provide some kind of caregiving assistance for an older relative, according to the Pew Research Center.

The reasons for intervention vary—Alzheimer's, arthritis, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, surgery, even an injury sustained in a fall. The caregivers themselves are also diverse—sons, daughters, spouses, even friends and neighbors. Regardless of the circumstances, the goal of family caregiving is always the same: to provide a loved one with a comfortable, caring environment in which to grow old.

Overview of Key Statistics

The 2015 edition of the State of Caregiving survey reveals a series of illuminating insights into the circumstances of family caregivers.

Here are 10 key conclusions from the survey:

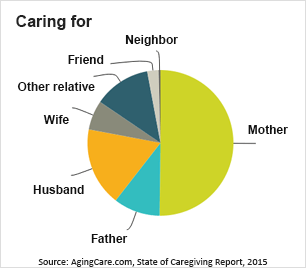

Moms are most likely to need care

Moms are most likely to need care

Fifty percent of family caregivers are adult children looking after an aging mother. Seventeen percent are wives providing assistance to an ailing husband. A much smaller, yet still significant, percentage are either taking care of their father (10%) or wife (7%).

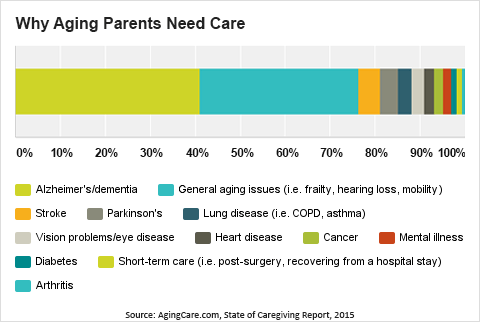

Dementia is the dominant concern

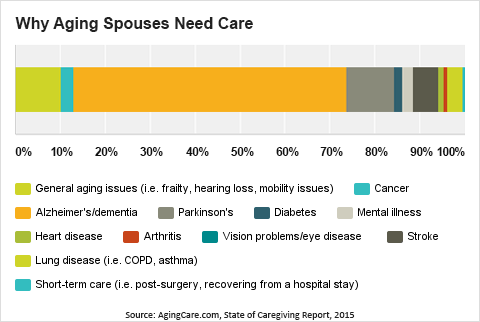

Alzheimer's/dementia and general aging issues (i.e. frailty, hearing loss, mobility problems) top the list of health concerns that require caregiving, with 51% and 23% of family caregivers, respectively, reporting that these conditions are the reason they must provide assistance to their loved one. Parkinson's demands the efforts of about 8% of the caregiving population, while stroke comes in a distant fourth, at 5%.

Long-term care is the norm

For the most part, family caregivers are in it for the long haul. Nearly 57% of caregivers have been in their role for more than three years.

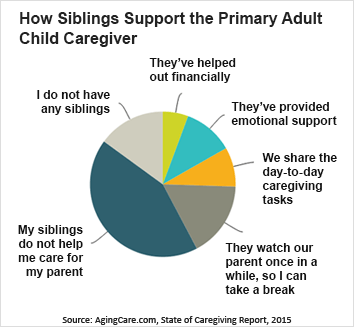

Sibling rivalry is real

Most adult child caregivers have between 0 and 2 siblings.

Most adult child caregivers have between 0 and 2 siblings.

In families with multiple adult children, the typical factor that determines who becomes a caregiver appears to be physical proximity to the older parent, as opposed to the age or birth order. Sixty-seven percent of adult children who are caregivers live less than 10 miles from their aging parents, yet only 40% of adult children who are caregivers are the eldest child.

Brothers and sisters, if they do offer assistance—43% of caregivers report receiving no help from their siblings—generally pitch in by either watching their parent periodically, so that that the primary caregiver can take a break (17%), or providing emotional support (11%).

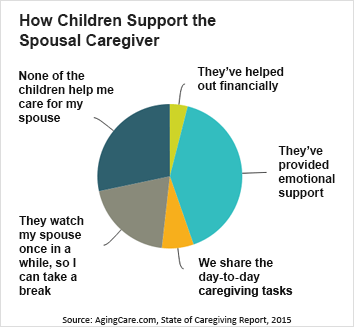

Most spousal caregivers have between 0 and 3 children, and 46% say that at least one of these adult children lives within 10 miles of them.

Most spousal caregivers have between 0 and 3 children, and 46% say that at least one of these adult children lives within 10 miles of them.

Adult children of spouses who are primary caregivers are slightly more helpful than the siblings of people caring for an aging parent—only 28% of spousal caregivers say their children do not help them care for their partner. Overall, emotional support and respite care are the top two contributions made by the children of spousal caregivers.

Older adults often live at home

Older adults overwhelmingly express a desire to age in place, and this trend does appear to be playing out the realm of elder care. Eighty-three percent of family caregivers report that their loved one lives either in their own home or the home of a family member. The remaining 17% of older adults in need of care reside in senior living facilities such as Independent Living, Assisted Living, Memory Care or a Skilled Nursing Facility.

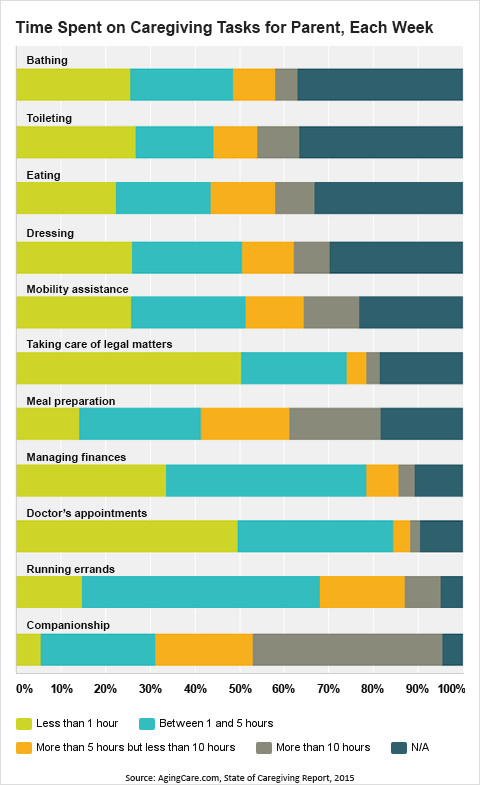

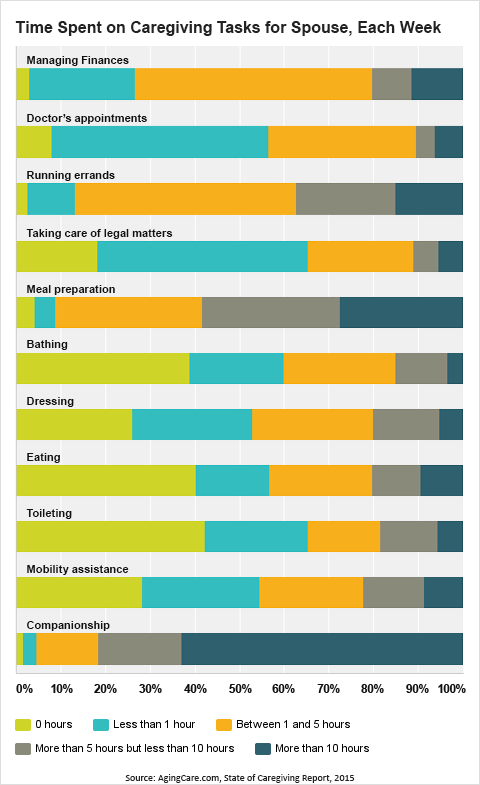

Companionship is the top caregiving task

Across genders and situations, the vast majority of family caregivers devote 10 or more hours each week to providing companionship for their loved ones. Other top tasks include: running errands, managing finances and preparing meals.

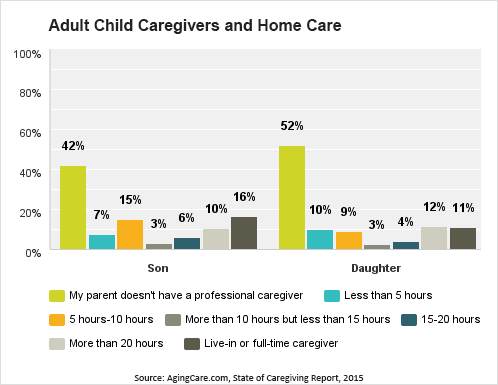

Men are more likely to hire home care

While 54% of family caregivers have not hired a home health aide (or other professional home care provider) for their loved one, men are more likely than women to seek outside assistance with caregiving duties.

Interestingly, guilt also appears to play a powerful role in determining whether a family caregiver chooses to hire a professional to help look after their loved one. The more guilt a family caregiver feels about their own ability to care for their loved one, the less likely they are to hire an outsider. Conversely, family caregivers who are less prone to guilt are more likely to make use of home care services.

Discussing money does make a difference

The average family caregiver spends between one and five hours each week helping their loved one with financial management tasks (i.e. paying bills, managing accounts, etc.). Fifty percent of family caregivers have either had to dip into their personal savings or take on significant financial debt to care for their aging loved one.

The vast majority of family caregivers (73%) have engaged in financial discussions with their loved one. Having a dialogue about money issues appears to reduce the amount of cash a caregiver has to contribute to their loved one's care.

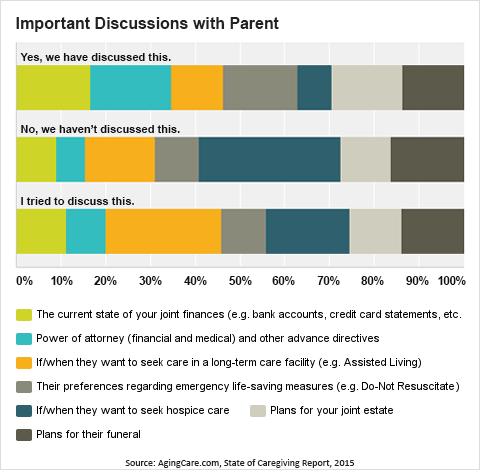

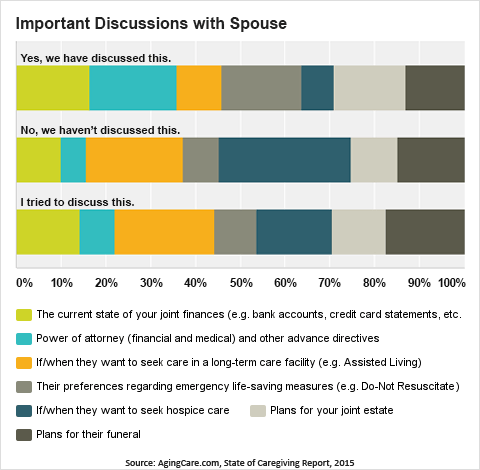

Families plan ahead, but avoid talking about hospice

When a loved one becomes ill, it's critical for families to have conversations about power of attorney (POA), financial planning and health care preferences.

The vast majority of caregivers appear to be having these conversations with their loved ones, with one major exception. The topic of hospice is still overlooked by 60% of families.

Caregiving can deal a major career blow

Becoming a caregiver for an aging loved one can deal a serious blow to a family caregiver's career. Since the vast majority of spousal caregivers are either in or nearing retirement when their partners start to require care, it is the careers of adult children that are hardest hit by caregiving responsibilities.

Forty-three percent of sons and 42% of daughters agree or strongly agree that their professional career has suffered as a result of their caregiving, while 15% of husbands and 25% of wives say the same.

One quarter of daughters had to quit their job to attend to a parent in need, compared to 17% of sons. An additional 29% of daughters and 32% of sons had to reduce their working hours to help care for their parents.

Having a sympathetic employer appears to be a key factor in keeping family caregivers in the workforce. Adult children with less-than-supportive bosses were far more likely to report having to quit their job or reduce their hours than those who had more understanding employers. As caregiving continues to become more mainstream, company policies will likely continue to shift towards more flexible scheduling and work-from-home options, in an effort to retain talented workers.

This list merely cracks the surface of what the State of Caregiving: 2015 uncovered. In the next sections, we'll expand upon our findings and compare two distinct sets of caregivers: spouses versus adult children, and men versus women.

Section 1: Spouses versus Adult Children

Despite being more than 65 million strong, the American population of family caregivers is often viewed as a homogenous group. Policymakers and program coordinators tend to overlook the crucial differences between people who are taking care of an ill spouse and those who are looking after an aging parent.

Most family caregivers (60%) are caring for an aging parent, while just under a quarter (24%) are looking after an ill spouse. The typical adult child caregiver is between 50 and 70 years old, while spousal caregivers tend to be slightly older—between 60 and 80 years old.

Health conditions

As far as ailments go, an overwhelming proportion of spousal caregivers are caring for a partner with Alzheimer's or some other form of dementia (61%). Parkinson's is the next most common health condition that leads to spousal caregiving, affecting 11% of the spousal caregiver population.

While a large number (41%) of adult children are caring for someone with Alzheimer's/dementia, general aging issues are also a major concern, accounting for 35% of adult child caregiving situations. This is one of the major areas where spousal caregivers and adult children differ—only 10% of spousal caregivers cite aging issues as the top reason why they became their partner's caregiver.

Day-to-day care

Nearly twice as many spouses (60%) spend 30 or more hours a week caring for their loved one, compared to 39% of adult child caregivers.

This could have something to do with differences in living situation between these two caregiver groups.

While nearly 87% of spousal caregivers live in the same house as their partner, only 35% of adult sons/daughters co-habitate with their aging parent. Adult children are also more than three times more likely than spousal caregivers to place their loved one in Independent Living or Assisted Living.

Hiring home care

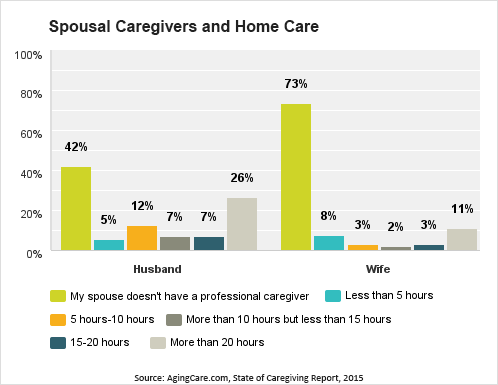

Spousal caregivers tend to feel less comfortable with the prospect of bringing in an outside professional to provide care for their loved one. Sixty-six percent of spouses abstain from hiring home care, and wives are less likely than husbands to employ home care services for their partner.

Spouses who have discussed their financial situation with each other in advance are more likely to hire home care services than those who haven't had this conversation.

Spousal caregivers who do eventually hire a home health aide appear to do so only when in dire need, as indicated by the 14% of spouses who say they require the services of an outside professional for 20 or more hours per week.

Adult children seem to be slightly more comfortable with the idea of seeking professional home care assistance, though more than 50% say they have not used such services. Again, great need appears to trump the desire to care for an aging parent personally—22% of adult children have hired a home health aide to provide at least 20 hours of care for their parent per week.

Talking it out

When it comes to having tough discussions about finances, future plans and legal issues (POA, DNR, etc.) an equal (and significant) percentage of adult child caregivers and spousal caregivers have talked through each topic with their loved one.

The one area that still appears somewhat taboo is hospice care. Only 32% of spouses and 8% of adult children have had this conversation with their loved one.

Financial considerations

The vast majority of adult children spend between $0 and $500 of their own money on their parent's care, each month. Approximately 55% of spousal caregivers report monthly care expenses in that range as well, though more than 20% say they spend between $500 and $1,500 per month on their partner's care.

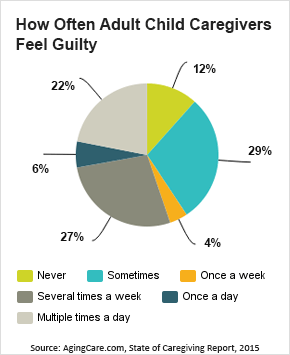

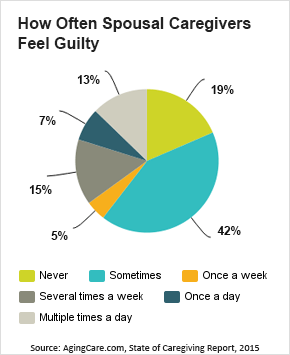

Emotional response to caregiving

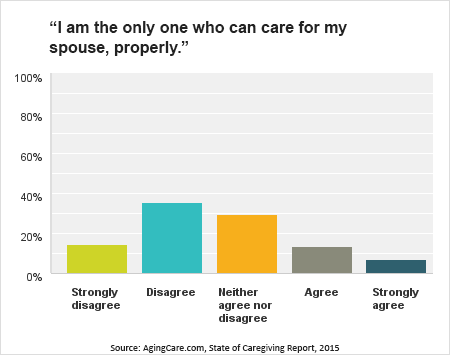

Adult children tend to experience more frequent feelings of guilt than spousal caregivers. Twenty-two percent of sons and daughters grapple with guilt multiple times a day, whereas only 13% of spouses say the same.

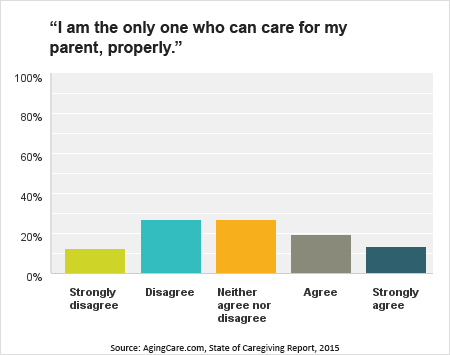

Adult children are also more likely to subscribe to the belief that they are the only ones who can take care of their loved one properly (34% versus 22% of spousal caregivers). This could be a contributing factor behind why adult children feel guiltier—if you believe you're the only one who can take care of your loved one properly, you're more likely to take on too much caregiving responsibility, and then berate yourself when you become overwhelmed.

Section 2: Men versus Women

Male and female caregivers may not be from Mars and Venus, but they do appear to approach caregiving from two distinct perspectives. Each gender has certain stereotypes attached to it and, when it comes to caregiving, some of these stereotypes ring true, while others are less black and white:

Women are the caregivers and the care receivers: True

An overwhelming percentage of caregivers are women—91% of adult child caregivers are daughters, while wives constitute 76% of the spousal caregiver population. Also, more than 50% of care receivers are either mothers or wives.

Men provide less hands-on care: Partially True

This also appears to be true…to a certain extent.

Care tasks: Both genders dedicate roughly an equal amount of hours caring for their loved ones each week. But daughters are more likely than sons to help their parent with tasks such as bathing, dressing/grooming and eating. On the flip side, husbands are more likely than wives to help their partner with these same, hands-on caregiving tasks. One possible explanation could be that husbands are simply too large or strong for their aging wives to bathe, lift, etc., forcing wives who are spousal caregivers to solicit outside assistance for these kinds of tasks.

Hiring home care: Regardless of whether it's a husband caring for a wife or a son caring for a parent, men are more likely than women to hire an outside caregiver. One particularly interesting finding was the apparent effect of children on a husband's or wife's tendency to seek out a home health aide to help care for their partner. Husbands were less likely to employ outside care if they had at least one adult child to help out at home, while the presence of an adult child actually made a wife more likely to hire home care. Having a sibling's assistance didn't appear to have much of an effect on whether an adult child of either gender would pursue the option of hiring an outside caregiver.

Women are more emotionally invested in caregiving: False

The majority of caregivers, male and female, husbands and wives, do periodically feel guilty about their ability to take care of their loved one. Women are only slightly more likely than men to report having feelings of guilt "multiple times a day." The most common source of this guilt is the feeling that the caregiver is not doing enough to help their loved one:

- "I just think I should be able to do better. Sometimes I am so mad that I am in this situation," a wife remarks.

- "No matter how much I do, things still slip through the cracks…I hate that!" says one husband.

- "Am I doing enough for mom? Am I being too selfish?" a son asks.

- "I feel like I fall short most days," says one daughter.

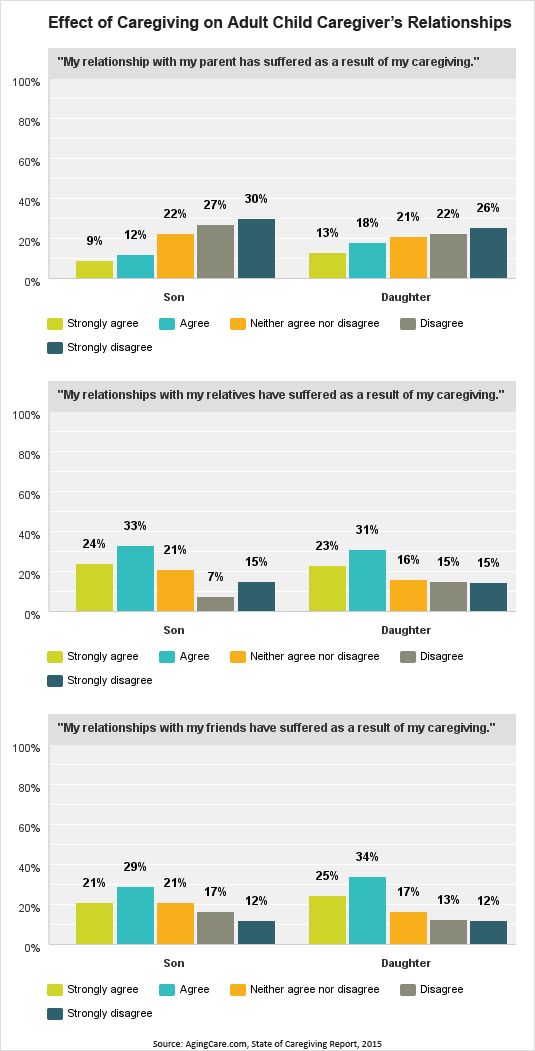

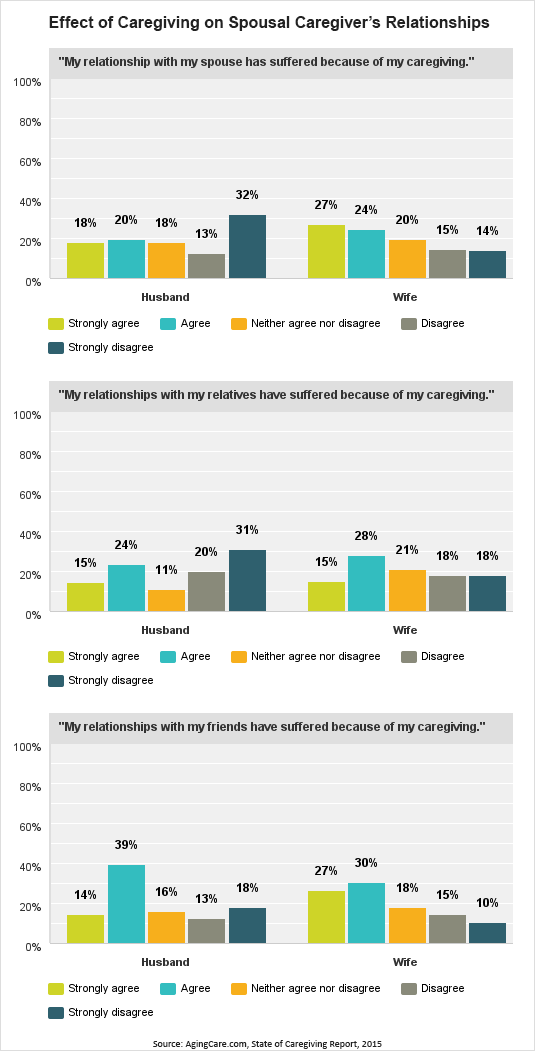

The one aspect of caregiving that does appear to emotionally affect women more than men is the realm of interpersonal relationships—especially the caregiver's relationship with the care receiver.

Thirty one percent of daughters and 51% of wives agree or strongly agree that their relationship with their loved one has suffered as a result of their caregiving, while only 21% of sons and 38% of husbands say the same.

Section 3: Caregiver Support Comes Online

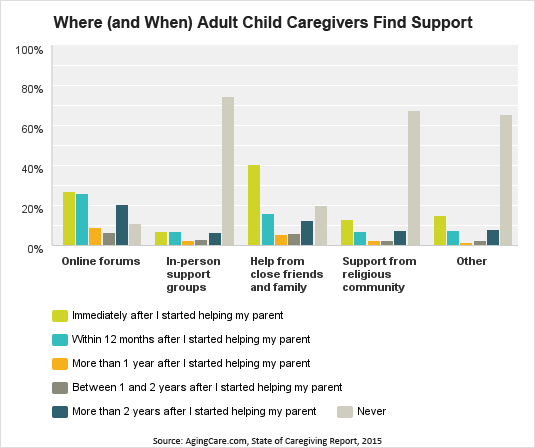

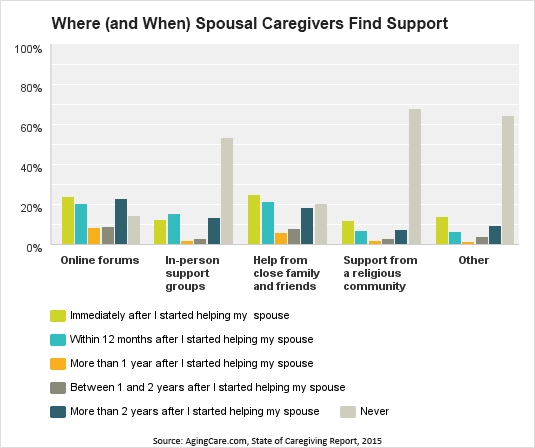

Caregiver support comes in many forms, from in-person gatherings, to programs run by religious groups, to online communities of caregivers. Close family and friends also play a pivotal part in helping caregivers cope with the stresses of their role.

Each support provider brings a different element to the equation.

Family and friends tend to be the people who are most well-acquainted with the caregiver and, typically, the care recipient as well. Their unique perspective allows them to offer highly personalized emotional assistance, and is probably the driving force behind why the majority of new caregivers immediately turn to close family and friends for succor.

Coming in at a close second in the caregiver support arena are online communities such as the AgingCare.com Support Groups.

More than a quarter (26%) of caregivers seek support on an online forum right after they begin caring for their loved one. By the end of their first year of caregiving, nearly half (49%) of caregivers have turned to an online community for assistance.

And they often find exactly what they're looking for:

"This website was a lifeline so many times," remarks a member of the AgingCare.com caregiver community. "Exhausted, confused, or sometimes feeling strong and helpful, I checked in every evening, and would come away with hope, a renewed spirit, and I ALWAYS learned something new."

"Thank you all, I am so grateful to everyone on this site," says another. "Your humanity, wisdom, and humor have saved me many times. You have given me the strength to change things for the better. I would have never made it this far without you guys. Thank you from the bottom of my heart."

Internet-based forums also offer caregivers the opportunity to give back by providing empathy and wisdom to their fellow caregivers. Some of the tips offered by respondents to the State of Caregiving survey are:

- "Take one step at a time."

- "Be prepared for a total change."

- "Even though you will have guilty feelings, always know that you are doing the best you can for your loved one. And somewhere inside, they know it and appreciate everything you're doing."

- "Research and discuss all options with your spouse/siblings and an elder law attorney. Don't make decisions based on guilt."

- "Make boundaries and stick to them before much of your life is over and you start to realize how much joy you could be having if you weren't stuck in an unhealthy-for-you situation."

- "Balance your life with friends and activities and don't just shrink into the caregiving world with no outlet."

- "Ask for help early. Don't assume everyone can read your mind."

- "Put systems in place, before you need them, so you can take care of your own needs."

- "I have several friends also taking care of their mothers—there is this unspoken camaraderie that we have surrounding our circumstances. The only advice I give them is to join these forums and vent because this is so difficult and painful for each of us."

- "Do your best and leave the rest."

Issue Spotlight: Cancer and Alzheimer's, a Tale of Two Support Systems

Alzheimer's and cancer are two of the most widely-feared diseases in America. People taking care of loved ones with either of these two conditions face a daunting series of challenges, and two different types of support systems.

A closer look at the caregivers

Cancer is one of the costliest diseases of aging; oftentimes outstripping the enormous expenses associated with Alzheimer's/dementia care. Cancer patients and caregivers also tend to be on the younger end of the spectrum; many of them are in their 50s and 60s, as opposed to Alzheimer's patients and caregivers, many of whom are 70 or older.

Caring for a loved one with cancer is often a shorter journey than caring for a loved one with Alzheimer's/dementia. The typical cancer caregiver reported occupying their role for less than three years, while many of the men and women who were caring for someone with Alzheimer's/dementia were in their position for five years or more.

Cancer caregivers also appear to feel ill-equipped to take care of their loved one, perhaps due to the complex medical nature of the condition. Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers, on the other hand, are more inclined than cancer caregivers to agree with the statement: "I am the only person who can take care of my loved one, properly."

Beyond the physical and financial obstacles that cancer and Alzheimer's/dementia present to caregivers and patients, lie the emotional trials of maintaining relationships while dealing with a dreaded disease.

The toll that cancer takes on a caregiver's interpersonal relationships largely depends on whether the caregiver is an adult child or a spouse. Most adult children who are caregivers find that their connection to their parent with cancer does not suffer much as a result of their caregiving, though their relationships with other family members and friends do take a hit. On the other hand, a large number (58%) of spousal caregivers of people with cancer find that their bond with their ill partner does degrade when they begin providing care. This trend also held true for Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers—with spouses reporting a more profound change in their relationship than adult children.

An understanding employer is key

As discussed in previous sections, caregiving can have a dramatic impact on a person's career. This is especially true for people taking care of a loved one with cancer, Alzheimer's or another form of dementia.

The percentage of adult children working full-time outside the home drops by 40% when they become a caregiver to a parent with cancer. Corresponding increases in the percentage of caregivers working part-time (either form home or outside the home) highlights the immense challenge of maintaining full-time employment while looking after a loved one with cancer.

On the Alzheimer's/dementia end of the spectrum, the onset of caregiving cuts the percentage of full-time, outside of the home workers in half, and nearly doubles the percentage of retirees. Indeed, 25% of adult child Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers and 18% of spousal Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers report having had to quit their job to care for their loved one.

Employer support is essential to helping keep a caregiver's career on track.

When asked to describe their experiences seeking employer support for their caregiving role, cancer caregivers did find some measure of assistance, while those caring for a loved one with Alzheimer's/dementia felt less supported.

Caregivers of parents with cancer were far more likely than caregivers of parents with Alzheimer's/dementia to feel that their employer was understanding of their situation (55% of cancer caregivers versus 37% of Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers). Adult children caring for a parent with cancer were also more likely to report receiving adequate support from their employer while caregiving.

More money, better support?

In 2015, the National Institutes of Health is expected to allot $5.4 billion to cancer research, whereas Alzheimer's is set to receive $586 million.

The bulk of these funds is dedicated to researching and developing better diagnostic procedures and treatments, but some money does go towards enhancing support services for the families of loved ones who are dealing with these conditions.

For many years, cancer has received an exponentially larger amount of federal funding, and countless advances in detecting and managing different types of cancer have resulted from this windfall.

But has more money actually resulted in superior support services for caregivers, patients and their families?

When it comes to seeking assistance from the government, cancer caregivers report that they feel more comfortable reaching out than Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers do.

But 70% of cancer caregivers feel that financial support from the government is ultimately lacking, while 66% feel the same way about caregiver support services offered by the government. Similarly, 63% of Alzheimer's/dementia caregivers were disappointed by the lack of government-provided financial and caregiver support they encountered.

Even though neither category of caregivers seemed satisfied with their experience with government support (or lack thereof), it's important to note that cancer caregivers are still more likely to reach out for help than people who are caring for a loved one with Alzheimer's/dementia.

Several factors could be contributing to this discrepancy.

First, Alzheimer's and other forms of dementia carry a powerful stigma that tends to silence the families who are affected by it.

The "War on Cancer," officially raging since 1971, has largely done away with any stigma surrounding that condition. Dementia, on the other hand, is a disease category that is just now gaining greater attention from the American public. Misconceptions and fears abound, causing caregivers and patients alike to feel apprehensive about asking for help.

And there's not as much information out there about how Alzheimer's/dementia patients and their caregivers can access assistance. When a person is diagnosed with cancer, their doctor can typically refer them to a wide array of physical, emotional and financial support programs. When a person is diagnosed with Alzheimer's or another type of dementia, there isn't a strongly structured support system to direct them to.

About the Survey

The State of Caregiving: 2015 survey dives deep into the demographics, financial circumstances, living situations and support systems of family caregivers, offering unprecedented information and insights.

The results come from an online survey of more than 3,300 family caregivers, carried out during January and February, 2015. The survey was conducted by AgingCare.com, the go-to destination for family caregivers, a website that attracts more than one million men and women caring for an aging loved one, each month. AgingCare.com is where caregivers discover that they are not alone, how to survive, and how to provide the care their loved one needs.

To learn more about the State of Caregiving: 2015 survey, contact us here.